On Thursday, December 11, it will be 15 years since Manezhnaya Square in Moscow trembled with the noise of tens of thousands of people. Around the same days in 2011, another large wave of protests began to gain momentum — the rallies on Moscow’s Bolotnaya Square.

These dates, separated by only a year but united by huge hopes for change, now seem like fleeting memories from a distant era — a time when mass street protests in Russia were still a reality, not a criminal act, and when not loving or supporting the authorities was considered normal, not suspicious or hostile behavior toward the state.

Fifteen years later, one can look back at these events only with bitterness and with a question that is not easy to answer: what exactly went wrong? Why did a large, active, multi-layered civil society and widespread awakening fail to become a turning point toward democracy and a world without Putin, instead leading only to the strengthening of a harsh autocracy? Memories of those protests are not nostalgia (after all, this is Russia’s internal matter, not Ukraine’s) but an attempt to identify and understand the decisive moment when Russian political history took a completely different — and, as it turned out in a few years, bloody — path.

Why did the mass protests of Russians in the early 2010s become effectively the last chance to change the situation for the better — and why were these chances not realized? UA.News political observer Mykyta Trachuk analyzed the question.

Manezhnaya Square: nationalist outburst and the first warning to the authorities

In December 2010, Moscow became the scene of events that did not quite fit into the pre-drawn picture of the country’s political landscape. After the murder of well-known football fan Yegor Sviridov by a person of Caucasian origin, tensions that had been building for years due to problems with migration policy and national relations suddenly and loudly exploded.

Manezhnaya Square, located just a few hundred meters from the Kremlin, filled with tens of thousands of people. It was a spontaneous rally, difficult to call a classic anti-government protest — it was more like a riot and an expression of rage. Its main tone was openly nationalist, “football-related,” and anti-Caucasian. Protesters demanded a fair trial and expressed deep dissatisfaction with the federal center’s national policy within Russia itself.

Although the square was dominated by representatives of right-wing and openly radical nationalist movements, the significance of these events went far beyond their demands. The Manezhnaya protest demonstrated two fundamental things.

First, “Manezhka” showed that Russia had a large, unrealized protest potential, capable of spilling onto the streets near the Kremlin even in the absence of a clear political program. Public discontent could be focused on specific social or national problems, but its scale was still threatening to the authorities. At that time, the president of Russia was Dmitry Medvedev, who had the image of a fairly liberal person and was nothing like the bloodthirsty propaganda monster he has become today.

Second, the authorities’ response was ambiguous and inconsistent. There were arrests and mass clashes with the police — but there was no harsh and systematic suppression of protests, as we would repeatedly see later. The government under then-President Medvedev partially engaged in dialogue, promising an impartial investigation.

And, surprisingly, it kept the promise. All the Caucasians involved in the conflict with the late Yegor Sviridov received prison sentences. The direct murderer of the Russian football fan, Aslan Cherkesov from Kabardino-Balkaria, received over 20 years in prison and remains behind bars to this day.

It was a moment when Russian autocracy had not yet grown into the regime it is today. At that time, it was only learning to uncompromisingly and harshly suppress any street activity. “Manezhka” became the first serious warning to the elites — a signal that society was no longer completely apathetic. At the same time, it was a lesson for the authorities themselves — a lesson they would learn very quickly.

Bolotnaya Square: spring of liberal hopes and Putin’s “Long Winter”

If the protests on Manezhnaya Square were a sudden explosion of rage connected to a specific trigger (the murder of a Russian youth by a Caucasian), the rallies that began on Bolotnaya Square in December 2011 were already a loud expression of broad and specific political outrage.

The formal pretext was massive election fraud in the State Duma elections, which provoked immediate rejection and disapproval among the urban middle class, intelligentsia, and parts of the business community. But soon the protest grew into something bigger: a stand against Vladimir Putin’s plans to return to the presidency for a third term, and later — against him personally, against a political system that denied the very possibility of fair competition.

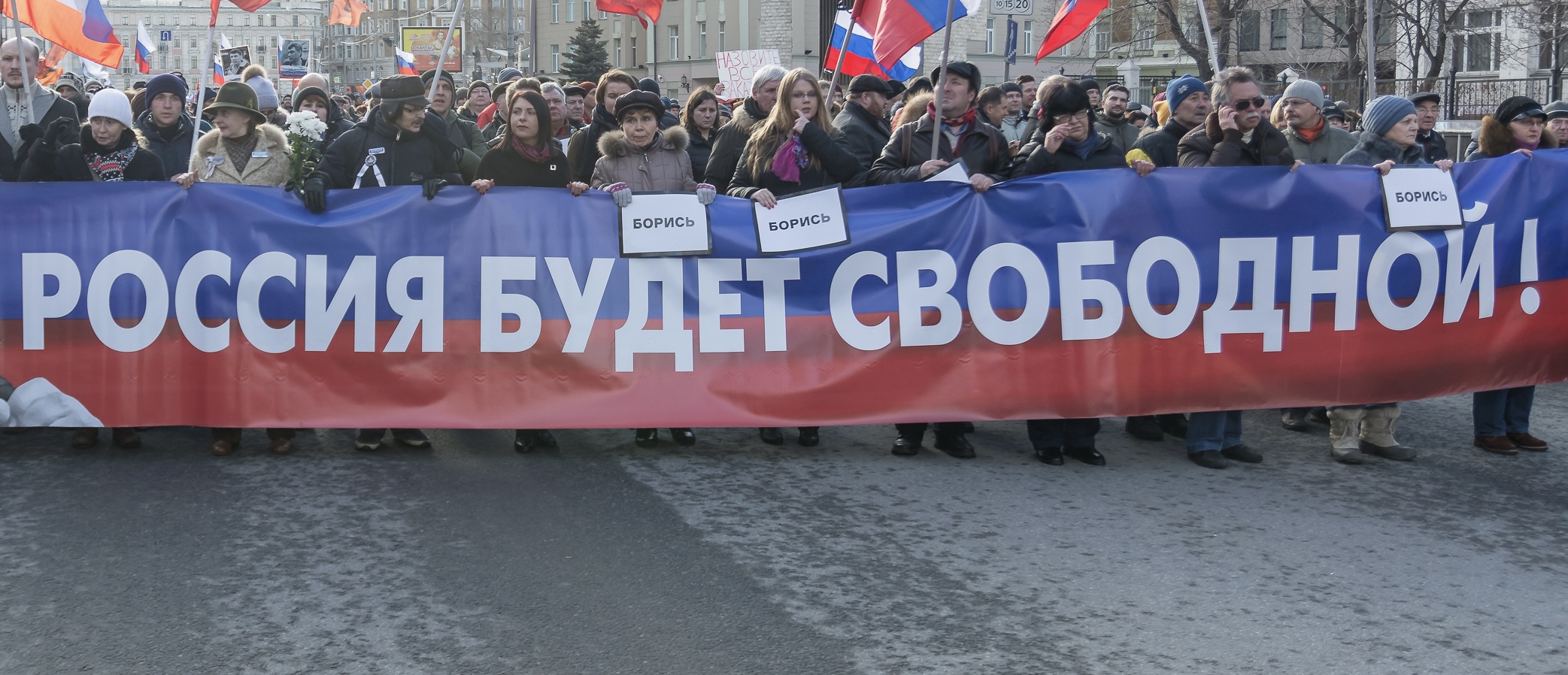

Unlike Manezhnaya, hundreds of thousands of people went to Bolotnaya Square and Sakharov Avenue in Moscow. “We want fair elections!” “Russia will be free!” — these were the key slogans of that protest.

It was already a broad civic movement, mainly liberal and democratic in orientation. However, the crowd was very diverse: there were human rights defenders, liberal youth — hipsters with white ribbons (hence the government media later derogatorily called protesters “white-ribboners”), veterans of political battles from the 1990s, right-wing movements (from nationalists and football fans to Eduard Limonov’s National Bolsheviks), as well as ordinary city dwellers tired of the authorities’ arbitrariness and constant lies.

Besides Moscow, protests spread to other cities and regions of Russia. Tens of thousands went out in St. Petersburg, thousands more in Kazan, Samara, Novosibirsk, Yekaterinburg, Tomsk, Arkhangelsk, Volgograd, Izhevsk, Chelyabinsk, and so on.

This “white ribbon movement” lasted intermittently until 2013, becoming the largest political protest in Russia since the early 1990s. There were attempts (though not very successful) to develop a common program, create coordination councils, and so on. On the wave of the protest, a new generation of politicians emerged, the brightest of whom was undoubtedly Alexei Navalny. Later he would experience multiple arrests, an attempt at deadly poisoning, and ultimately die under mysterious circumstances in a Russian prison in 2024.

Eventually, all this “spring of hope” associated with the Bolotnaya movement gradually turned into a long “political winter.” The authorities, initially openly bewildered by the scale of the rallies, quickly organized and moved to a strategy of harsh confrontation. Mass arrests and prosecutions of activists began. The forceful dispersal of the Bolotnaya rally on May 6, 2012, became a symbolic and very important “Rubicon,” after which it became clear that the protest was failing.

At the same time, the Kremlin launched a counter-mobilization, organizing its own “people’s” rallies (with state employees and pro-government organizations paid by the president’s administration) and deploying a powerful propaganda campaign to discredit protesters as “Western puppets.” Despite its scale, the protest gradually began to fade.

It lacked a clear unifying structure, a concrete post-rally plan, any final goal, or understandable methods to achieve it. Putin, returning to the Kremlin in March 2012, immediately made it clear that there would be no concessions to the “white-ribboners.” The annexation of Crimea and the start of the war in Donbas in 2014 redirected public energy into “patriotic” and pro-government mobilization, putting a final end to the history of Russia’s liberal protests of the 2010s.

The last chance for democracy: why it didn’t work

Today, 15 years later, these events appear not just as a page of history, but as perhaps Russia’s last real chance for democratic development. In modern Ukraine, the idea that Russia once had significant liberal-democratic and protest potential is unpopular. Most Ukrainians consider Russians “brainwashed,” totally supporting the authorities and incapable of any act of defiance.

And, of course, there are understandable reasons for this. The full-scale aggression against Ukraine caused a small surge of anti-war protest in February 2022 (tens of thousands went out, over 15,000 (!) were detained), but the authorities quickly and harshly suppressed these rallies, and as of December 2025, Russia experiences total “death of politics.”

However, the reality is more complex. Dissatisfied people and anti-Putin sentiments did exist and were widespread just 12–15 years ago. They exist even now, though not visible to the naked eye. At the time, when the Kremlin regime was not yet monolithic, when public debate was ongoing, and the economy was more open, millions believed in the possibility of change through protest. But the chance was lost due to a series of fatal mistakes and objective weaknesses of the protesters.

It all began with organizational fragmentation. The opposition was divided into many mutually hostile groups: liberals, nationalists, leftists, rightists, etc. Radical activists clashed with those seeking dialogue, the “systemic” opposition could not find common ground with the “non-systemic.” The protest remained mainly a “rally of dissent,” more a “senseless and ruthless Russian riot” than a thoughtful movement with a clear strategy and hierarchy.

It was politically “toothless,” unable to overcome the pressure of propaganda, failed to offer a convincing alternative vision of the future that could attract not only major cities but also the broader regional masses. Most importantly, it underestimated the regime’s readiness for harsh forceful response and its ability to mobilize its own social base through ideology of conservatism and imperial revenge.

Fifteen years later, the picture is sad and even tragic. Large-scale protests no longer exist. The most active participants either left the country, received long prison terms, or completely withdrew from politics.

Protest leaders are dead or deceased (Alexei Navalny, Boris Nemtsov, Eduard Limonov), or are in prison or exile (Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Garry Kasparov, Mikhail Kasyanov, Ilya Yashin, Dmitry Gudkov, Yuri Dmitriev, Maxim Katz, Ilya Varlamov, etc.). Those who remain are either co-opted by the Kremlin and integrated into the existing political system (Grigory Yavlinsky, Ksenia Sobchak) or fully marginalized. The space for legal political activity in Russia as of December 2025 is completely destroyed.

Knowing how to protest — not how to win

Russia of the early 2010s demonstrated that it knew how to protest — massively, broadly, and through genuine civic outrage and sincere desire for change. Protests on Manezhnaya and Bolotnaya Squares were symptoms of a deep legitimacy crisis of the regime, which at that time could still have been resolved through democratic procedures and real reforms. But this chance was lost. Instead of internal transformation, the Russian state chose the path of autocracy, conservation, revanchism, external aggression, and internal consolidation of autocratic and sometimes even totalitarian practices.

For Ukraine, this plays a direct and immediate role: had the protests succeeded, most likely there would have been no Putin, no Crimea and Donbas, and no full-scale invasion in 2022. However, history does not tolerate conditionalities, and the words “if” and “had” are unfortunately irrelevant here.

At the same time, history is not predetermined or programmed in advance. Experience shows that societies can awaken even after the longest political slumber. The experience of the 2010s protests remains in collective memory as proof that the desire for freedom and justice in Russian society has not disappeared forever. One hopes it is only temporarily suppressed by fear, propaganda, and repression.

When the Putin regime, like any other dictatorship, eventually weakens under the pressure of internal contradictions or external defeats, the streets of Russian cities may once again come alive. The question is whether a new generation of protesters will learn the lessons of their predecessors.

The chance lost a decade and a half ago cost Russia, Ukraine, and all of Europe too much. Next time, there must be no mistakes or “half-measures.”