A restraint bordering on coolness, which is felt even through the screen. Lyudmyla Huseynova – a volunteer from Novoazovsk (Donetsk region) – spent more than three years in the infamous torture center “Izolyatsiya” (a former cultural center in Donetsk) and Donetsk SIZO 5, where she was imprisoned for “extremism.”

While recounting the days, or individual moments snatched from the total fear of inhuman existence, the screams of prisoners over whom 24/7 abuse was inflicted, Lyudmyla’s voice remains consistently calm. It’s as if she left her emotions back there, in the cell: precise speech, honed phrases, the main goal – not to complain, but to convey a message to society: save civilian prisoners too, don’t forget to record their names in the exchange lists.

This is not the story of a traumatized victim, but rather a pragmatic report from a person who is eager to live and has a critically important mission – to become the voice of those still behind bars.

Before her arrest in 2019, 60-year-old Lyudmyla Huseynova, a safety engineer, was a quiet heroine. For five years after the occupation, she cared for orphans from the Novoazovsk orphanage, who lived practically on the frontline. Her “crime” was clothing, candies, and books in Ukrainian, which she and her husband brought to the children. And above their house flew the blue-and-yellow flag. For all this “criminal activity,” Lyudmyla was literally kidnapped by armed men in military uniforms while she was going to work, subjected to a “search,” and thrown into prison.

The cold-bloodedness with which she details the horrors of imprisonment has only one crack. Lyudmyla’s voice trembled once when she recalled an unexpected act of humanity from her criminal cellmates: they wished her a happy birthday in Ukrainian. This brief flash of warmth confirms: beneath the armor lies deep trauma. Today, Lyudmyla Huseynova talks with a UA.News journalist to explain the main philosophy of survival: freedom is having a choice. And if we, free people, can choose whether to listen to the suffering of others, those who remain behind bars have no right even to choose a neighbor on the bunk.

How long can one talk about prison?

It’s painful, and also heavy and psychologically difficult. Three years have passed since my release, yet I still do not have peaceful sleep – that’s also true. If it concerned only me, or my suffering, I wouldn’t say a word, I would go abroad or just take care of myself, because my health would require better care.

On the purpose of publicity and forgotten prisoners

This is fundamental. For me, the only goal is to draw attention to women who remain in captivity.

I was shocked when I returned three years ago that no one knew about these women, about us, about what has been happening in the temporarily occupied territories, starting in 2014. When I start talking about women who have been in captivity for seven, six years, people are surprised and say: “How? The war only started in 2022.”

This is unfair to people who lived, are living, survived (not everyone survived) in the occupied territories, who have been in captivity since 2014. Today, the number is staggering: almost 20,000 civilians… The number is very approximate. We generally do not know how many people were tortured in this captivity.

Choosing a pro-Ukrainian position instead of instinctive self-preservation

Despite the fact that I have always spoken Russian, even when I spent summers with children in my grandmother’s fully Ukrainian-speaking village of Yalanyets, in Vinnytsia region. We were teased a little, saying, “Oh, city people have arrived.” But we weren’t beaten for speaking Russian, weren’t forced to speak Ukrainian. So, I always considered myself Ukrainian and cannot understand how someone could deny being a citizen of their own country.

I saw employees who yesterday had sworn allegiance to Ukraine, sang the anthem, held their hand over their heart, hung flags in offices, and the next day, after the occupation, pledged allegiance to Russia. I do not understand this… I do not understand!

For me, these people, traitors, have no value, because tomorrow they will just as easily renounce another citizenship, their own families.

About the dossier

Yes, I knew that the enemy had a dossier on me, starting from the day of the occupation. Many who had a pro-Ukrainian stance had folders. But I always thought: well, they’ll just expel me from the occupied territory, as if deporting. However, I really couldn’t imagine that “Izolyatsiya,” such horrors, could exist in modern Europe, in our European Ukraine, and that people could do this… in the 21st century!

Trust in people after release

Today, I have some problems, perhaps, with trust. But that does not mean I will hate a person. I see people here, in the free territory of Ukraine, different people, with different attitudes toward me, my experiences, and the events that occur.

People without critical thinking, people who do not interest me – I do not want to waste time communicating with them. I am ready to talk and discuss with those who have their own opinion but can justify it critically. And if a person is stubborn, does not want to hear another opinion, and takes their own as the only important one…

Was there a moment in the cell when doubt crept in: “Was my position worth it?”

Not a single thought like that. Every day I was there, with each very scary moment, I was sure that I had done everything right.

I realized: I am here because I am different. I saw cruel people around me, who made this prison, people I never wanted to be like. It pleased me that I suffered only because I am not like them. The most terrifying thing for me was to become like them, in behavior, in submissiveness.

Yes, there were people who adapted to survive. I do not judge them, because it is scary, it is difficult. I value the fact that I did not break myself to become what I never wanted to be.

Moments of despair

There were moments when I simply did not want to live, that’s true. When I closed my eyes, I thought: “God, make it so I never open them again. So I never see this again. I just cannot anymore.” But the eyes opened, and the horror continued. I had to live.

How to sleep knowing that tomorrow there will be more abuse

It was impossible to sleep there at all, because I was held in a cell with 20 criminal offenders. There was no understanding of silence, darkness, or quiet time. Constant noise, fights, a TV with Russian propaganda running around the clock, lights never turned off.

Sometimes I dreamed of being taken for interrogation. I knew I would be beaten, but at the same time, it was an opportunity to move a little. And when you sit for days in a small, smelly cell, the worst is the feeling that you are about to crash into a stone wall, to break it.

I once studied psychology and remembered that you can hold your breath during a panic attack. I often did this exercise. And I dreamed. If I climbed to the top bunk, there was a tiny grated window, at least I could see something. And I dreamed of it all ending, that they would rescue me. I imagined the doors of the cell opening wide, and our soldiers from the Armed Forces of Ukraine on the threshold. Silly stories, like in comics.

Then with dreams I returned to my city. Already de-occupied, under Ukrainian control. But I realized I would not live there. My house is empty, I walk the empty streets. The only thing that hindered me in these dreams was that I could not figure out what I would look like, what I would wear. Three years without a mirror, I had not seen myself. Only my hands, they were very thin, and my clothes hung off me, bones sticking out. So I could not determine what I would look like when returned from prison. Skirt, pants, suit? Such feminine things, they helped a little to escape from the surrounding horror.

Among criminal offenders

For the first six months, my cellmates provoked me a lot because we were from completely different worlds. There were different incidents, like someone threw a makeshift knife at me. I never used swear words, for example. And they had never seen anyone like me. These women and their environment speak exclusively with foul language, use drugs and alcohol. That is their norm of life. Yet, I did not feel hatred toward them. As much as possible, I did not violate their personal boundaries, I spoke as with anyone else.

Rather, I wanted to understand the nature, for example, of a woman who killed her husband and made a shashlik out of him on his birthday. Because during the celebration, food ran out, and something had to be eaten. And that woman killed her two four-month-old children. Why did she do it? I wanted to understand why they do not feel remorse, why they can sleep, why what they have done does not haunt them nightly. They did not worry about what they did. And when I thought I heard the most terrible story, new arrivals came with even more horrific experiences.

True, the cell had many mentally ill individuals, awaiting a court decision. Later they were transferred to psychiatric hospitals. This was another unpleasant moment when you are constantly on edge, because with such an environment, anything could happen.

They called me “crazy Ukropka,” but eventually got used to the fact that I was confident in my beliefs and would not conform, I am the way I am.

Paid for language with cigarettes

There were several women in the cell who specifically went to the occupied territories to fight for Russia against us. One of them, “Mishka,” from Vinnytsia. A heavy, strong girl. Together with her friend, they came to visit a civilian couple, drank, and then raped the couple and ultimately tortured them to death. Mishka was Ukrainian-speaking by birth, and I started learning Ukrainian in the cell, so she helped me with words I could not recall. When my sister passed me cigarettes (the prison’s magical currency), I asked Mishka to speak Ukrainian with me, about anything. Ten minutes of Ukrainian for one cigarette. And she had such a melodic Vinnytsia accent, it was so beautiful that everyone smiled, not just me.

Unexpected act of humanity

I turned 60 in the cells. At midnight, the TV suddenly turned off. I separated my sleeping place with an improvised screen, hung a towel to shield myself from others. And suddenly, this silence, I thought something happened. I lift the towel, and they stand together in the middle of the cell and in unison say in Ukrainian: “Happy Birthday.” It was very touching, unexpected. A very valuable moment that showed me that not all humanity had died in those women. And we laughed…

Book with black pages

Yes, from the pages of my diary we plan to publish a book. I wrote nine chapters and reached the point I do not remember at all. Does the body resist remembering it? I cannot recall these pages. When I simply reach these memories, I feel very nauseous.

I was offered to make black pages in the book, simply black sheets of paper. This is probably a very good idea, but there is not enough time to finish the book yet.

The hardest thing to explain to free people about what was experienced

There was a meeting, where I was invited by wealthy, self-sufficient women, living their lives. It was very important for me to convey what is happening with our civilian prisoners, hoping that their voices would amplify my message to society and the authorities. They would hear us. But one of them came up and said: “It’s so hard for me, I don’t want to deal with it, I don’t want to hear about it.”

To free people, I want to convey only one thing. They have the most valuable thing – choice. Any choice. We can go out and buy a bun or a poppy seed baguette, walk through the park or walk the streets. Communicate by phone with someone we like and block those we do not want to hear. We have freedom. These girls, these civilian prisoners, have no choice. No possibility to open the door and leave. No possibility to choose who is in the cell 24/7 for three years. No possibility to get medical support or a pill. Most likely, you die if someone does not have mercy to provide help.

There is not even certainty that if you die on the bunk, your body will be returned to relatives, not left to rot. I saw bodies with rats running over them. There is simply no choice. So when you have choice, freedom, however difficult it is, you can survive and live.

“Where were you when Donbas was being bombed?” – how she answers propagandists’ questions

I was in Donbas when it was being bombed. And I saw who did it. And I have numerous proofs of this. We all saw from where the equipment came and from which side we were bombed – from the Russian Federation.

When they tell me the war started because of us, the residents of Donbas, I will give examples of civilians who were tortured for displaying Ukrainian flags above their homes. Like Vasyl Kovalenko. He is a hero to me. He was tortured, beaten, brought home with mangled hands. And he hung the Ukrainian flag again. They killed him after that. There are hundreds of such people.

Who started the war? Those tens of thousands who were in captivity? Are they guilty? Those who did not survive in these torture chambers, and we don’t even know their names? Then I have a counter question – why does Ukraine still not know what happened and continues to happen there?

The greatest shock after returning

I was shocked by people’s unawareness of what is happening in prisons, the number of civilian prisoners, and that society does not know or does not really want to know. And the state does not want to know anything about these unfortunate people. We try to return military personnel by all means, but civilians receive almost no attention.

I was shocked by the words of a state official who was supposed to oversee prisoners: “Do not draw attention to civilian prisoners, because it increases their value in exchanges.” She tried to assess people. What value? People have been there for seven years! What else can there be in terms of value? They gave more than their life. They did not see their children grow. What value are we talking about? Why should the world not know about these ruined lives, about these people?

I was shocked by the working “P’yani Vishni,” “Bilyi Nalyv” in central Kyiv, on Khreshchatyk. A noisy party, music. Someone drinks and has fun. For me, it was, to put it mildly, incomprehensible.

I was shocked when I began reading or hearing about people trying to find any way to go abroad. It seemed to me that this cannot be in a country where a war is ongoing.

The world and people after “the Isolation prison”

Something has changed. People hate people. War amplifies each person’s characteristics. I do not like when people fill themselves with hatred.

I fully understand their feelings. But we have an enemy, and you should not fill yourself with this hatred and turn that malice against each other. And remain with a sober, cold head, realizing: if it’s war, the enemy must be destroyed on the battlefield. The enemy must be punished. I am categorically against general amnesty, which they have begun talking about now. For example, amnesty for doctors who performed their duties regardless of the patient. But criminals who tortured people, deliberately did not provide medical assistance – they must be punished.

Life after the exchange

I still haven’t registered my pension. My husband and I rent housing; he works hard to pay for it. No one obliges me to protect the interests of prisoners. Maybe this is the meaning of my life. Yes. One reason is awareness of what the girls endure there. Every minute I live here, every time I speak about prison, I momentarily return there, to these cells. Smelly, terrible. I start to suffocate because I know what it’s like THERE. And I do not want our girls to be there.

The vow made in the cell

When they led me out of the cell, Olga somehow sensed I was being taken for exchange (we did not know). She grabbed my hand and cried: “Just don’t forget about us.” I will remember her eyes for life. At the moment I stepped over the cell threshold, I already knew well what I would do in freedom. Olga has no relatives in free Ukrainian territory. There is no one to speak for her, no one to fight for her.

I am sorry that even if these girls have relatives, husbands, for example, they cannot, do not know, are afraid, or see no point to fight, to loudly speak about their relatives. I note that at events supporting civilian female prisoners, there are practically no men.

New Year’s wish

Our common wish is peace. My additional wish is the unconditional return of all girls from captivity. I insist that we cannot conduct any negotiations to establish peace if all our civilian and military prisoners are not returned. Military personnel are protected by international laws, but civilians, unfortunately, are not.

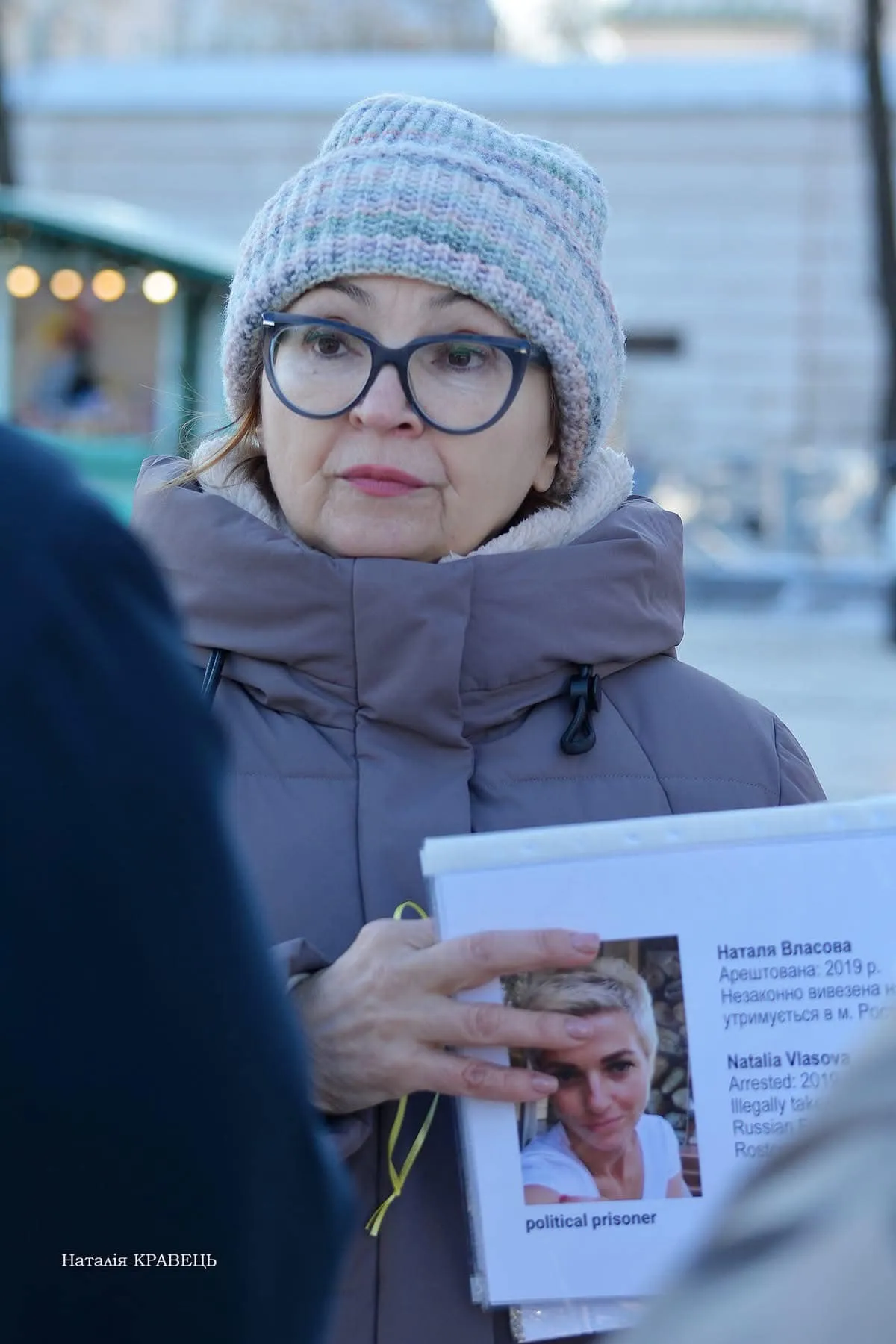

Yesterday, I spent the day with the daughter of Natalka Vlasova (also a prisoner who spent seven years in Izolyatsiya). Julia’s daughter turned 11. I returned in the morning from a trip to The Hague, picked up the girl, and we attended a festive event together. I am grateful to Vadym Filashkin, head of the Donetsk Regional State Administration, who provided us with funds; we went to a shopping center, bought the child a phone, shoes, clothes, and some other girlish things. We made this child happy.

Julia has been celebrating holidays for seven years without her mother. After the children’s event organized by the Donetsk Regional State Administration, we said that St. Nicholas also wants to make her another surprise (meaning we would go to the mall). And they asked: “What would you like?” Julia replied: she wanted her mom. It’s hard to convey these emotions. I would very much like to make this holiday for her, as her mother would.